We’re huddled in a conference room, trying to map the next move for our digital payments solution. The engineering lead wants a build to test the transaction-execution-happy-path end to end. The product manager wants to validate market fit. And the stakeholders just want proof that the thing can be built in the first place.

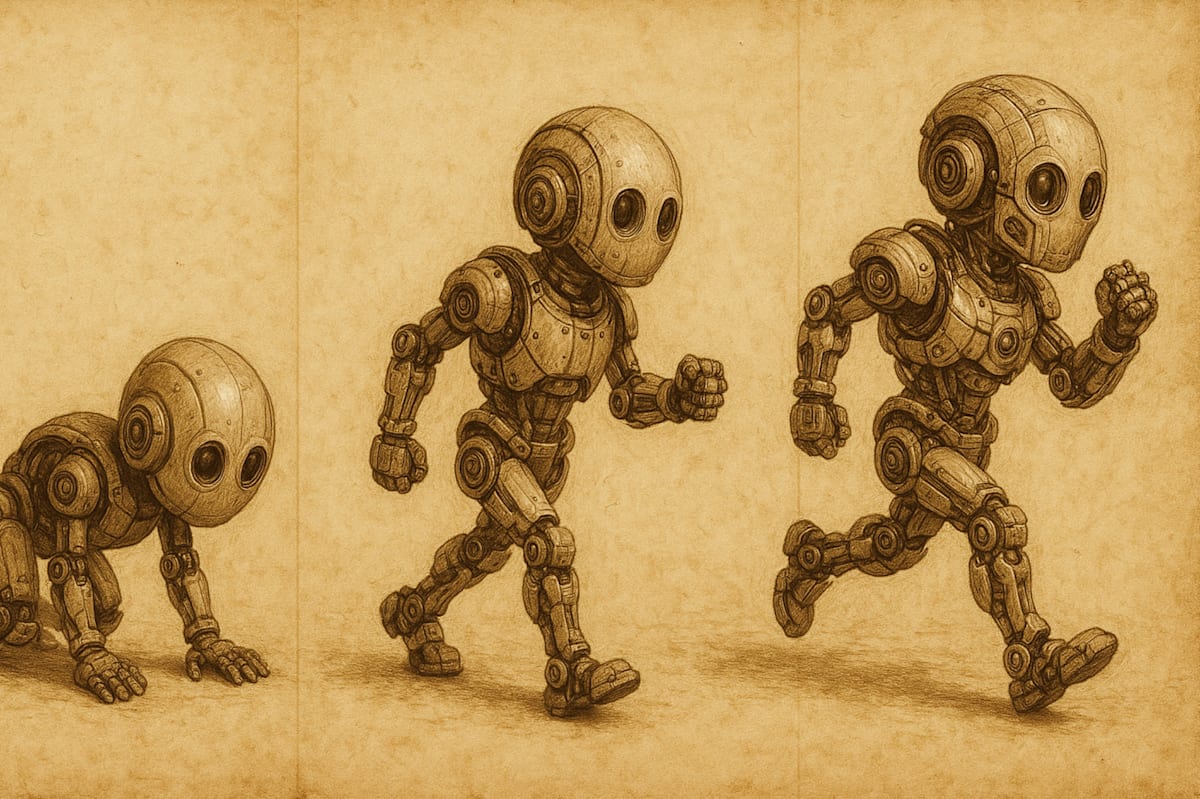

At first glance, it looks like they’re all at odds. But look more closely and you start to make out a sequence. Turns out they’re not arguing — they’re chasing different parts of a natural progression. The Stakeholders want a Proof of Concept (POC), the engineer wants a Prototype and the product manager wants a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). POCs, Prototypes, and MVPs aren’t competing approaches. They’re evolutionary stages — each one answering a different question in the journey from idea to product.

From “Can we build it?” to “How should it work?” to “Will anyone actually want it?”

Something fun happens when you stop looking at them as one-off bets and start seeing them as a connected path.

Stage 1: The POC

The Proof of Concept answers one thing and one thing only: Can this even be done?

This is your technical reality check. It’s not for customers. It’s not for the market. It’s for you — checking that you’re not chasing a mirage.

A friend of mine was working in blockchain payments. The POC was beautifully blunt: a command-line tool that could process a transaction through their proposed chain. No UI. No auth. Just a bare-bones flow proving the guts of the system worked. Two weeks, one API, zero fluff.

And that was the point. The POC wasn’t the product. It was the foundation. Once the technical core held up, the team had permission to move forward.

Stage 2: The Prototype

With the POC the rearview, the question turns to: How should this work for real users?

This means interface, interaction, and experience. It’s still early but the prototype brings the concept out of local and into something others can use.

This is where blockchain guy turned the CLI proof into a limited-access tool with a working UI and real user flows. No scale. No polish. Just something usable enough to walk through the experience and spot where it breaks down.

This step too often gets skipped. Teams race from POC straight to market, then wonder why users can’t figure it out. The prototype phase is where you catch those issues — before they become costly, public problems.

Stage 3: The MVP

If you’re here, you should’ve already cleared two major hurdles: It can be built and It can be used. Now comes the third: Do people actually want this?

The MVP isn’t a trimmed-down product. It’s a market probe that happens to function. It’s your prototype, with just enough hat to live in the real world, with real users, solving real problems.

Your early adopters don’t care that you solved a gnarly technical challenge. They care that you saved them time, money, or effort. The MVP proves — or disproves — that you’re solving the right problem for the right people in the right way and give you data you can use to pivot.

Stage4: From MVP to MSP

Great MVP — now the hard part. Once market demand is validated, you make the next leap: scale.

Here’s where we get upside down very quickly. Often we try to scale our MVP — a tool built to learn, not last. Systems start buckling. Customers churn. Technical debt metastasizes.

What you need now is a Minimum Scalable Product — the MSP. It’s not a pivot. It’s a rebuild on firm, proven ground. The same proven functionality from the MVP, but engineered for growth. Different infra. Different data models. Different performance thresholds. Because the question now is: Can we reliably serve everyone, not just our test group?

The Real Cost of Skipping Stages

We often skip the POC and build beautiful prototypes — that can’t actually be built. Or we skip the prototype and go straight to the MVP — only to discover the UX is a puzzle no user wants to solve. And worst of all, we try to scale an MVP like it’s production-ready. It (almost) never is.

What follows is a painful cycle: feature creep, hotfixes, patches, rework — a product that buckles under its own success (or gets set adrift while the team chases something new).

Skipping steps doesn’t accelerate progress. It compounds risk.

The Discipline to Progress

When your POC works, it’s tempting to slap on a UI and ship. When your prototype gets good feedback, the instinct is to go live. Let’s go! Is it done yet?!

But speed isn’t the point. Clarity is the point. Each stage earns you the right to take the next step. And if you cheat the progression, you pay with time, effort and delays when you can least afford it — with real users.

Take a minute. Ask: What stage are we actually in? What are we trying to learn? If the prototype’s being used as a sales tool, stop. If your MVP is buckling under traffic, stop. Step back. Reframe. Reset.

The goal isn’t four separate builds — it’s one coherent, validated, scalable product. A journey from idea to impact, paved with the right questions at the right time. Now, is it done yet?!